Almost everyone reading this has heard of the Titanic. A heart breaking tragedy indeed. But very few would have heard of a similar tragedy that occurred during the Indian sugar indenture.

In 1859, the ship Shah Allum carrying indenture coolies set sail from Calcutta to Mauritius. It caught fire and sank on its way. ALL seventy-five crew members were rescued. Only ONE of 400 indenture coolies managed to survive.

It is a tragic story that is almost unknown and rarely told in any history book. The information available about this tragedy is also sparse. Barely a few documents refer to it and no official records or pictures. After all, the passengers of “Shah Allum”were but poor indenture coolies.

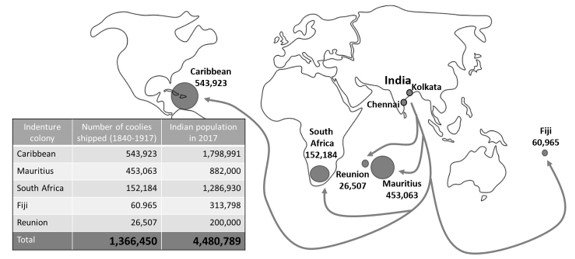

The ship journeys of the 1.3 million Indian indenture coolies provides a window into their plight, helpless but hopeful. The ships left from 2 ports – Kolkata (Calcutta) and Chennai (Madras). About 60% of the coolies were shipped from Calcutta and 40% from Madras port.

The indenture journey

Source : World map from istockphoto. Illustration by Yajusha Krishna

The voyages were long and weary, taking almost four months in some cases. In the early years of indenture teak (Wooden) vessels were used. By 1850s, the larger vessels carried about 300 passengers. By 1860s, the Nourse line of even larger ships started carrying coolies. After 1870s, steam ships were used which reduced the travel time to about 50 days.

In most of the journeys, the coolies were packed like sardines in the tweendecks (The deck between the two decks, the main deck and the Steerage (lower deck) which usually held cargo). On some vessels this deck was only about four feet below the Main Deck, and at the ceiling hieght of about six to eight feet. In the age of steamships, the coolies had to stay in the Steerage area. So, throughout the indenture journeys, the coolies had to survive for months in cramped, unhygenic and overcrowed conditions.

Here are some notes from the ship doctors of ships like the UMVOTI that brought coolies to Natal in 1886

Rice sifting : The rice had lot of stones and gravel. Every morning, the women on the ship had to clean the rice. On days when it rained or had heavy winds, this could not be done, so the coolies had rice with lot of gravel and hardly edible. Sometimes, they just threw the rice overboard and went hungry and on other days, were just forced to eat. This was also the cause for dysentry, diarrhea and other illnesses.

Dr. George Paterson, surgeon on the Umvoti, which arrived in Natal in 1886 was accused of raping several women, who gave depositions to magistrate Finnemore on 16 dec 1886.

Source : Indian Indenture by Goolam Vahed and Ashwin Desai

Here are some images of the ships that carried coolies in those days.

Source : wikipedia

My great grandfather went on the UMKUZI, an enormous steam ship that carried 614 coolies to South Africa in six weeks.

The indenture coolie ships were a huge melting pot of people from all religions, castes, and colors. Golla (shepherds), Chamar (untouchable leather workers), Dhobi (washermen), Kumhar (potters), Uppara (salt workers), Kapu (agriculture workers), Brahmin (the highest caste in Hinduism, who are priests), Saiyid (Muslims with noble ancestry), Rajputs (Warrior caste), Pathans (Muslims speaking Pashtu from the Pakistan, Afghanistan region), Reddys (Land owning higher caste), Qassab (Muslim butchers), Teli (oil pressers), and more. In those days (and in some parts to this day), in India, lower caste people were forced to live outside the villages and the upper caste Brahmins stayed in their own separate neighborhoods. If a Brahim touched a untouchable or the other way around, the Brahmins would bathe and perform rituals to get rid of the impurity. The untouchables would be punished for the grievous crime of polluting the Brahmin with their contamination.

But on the ship, it would not be the same. Coolies from the higher castes like Brahmins and the Rajput started protesting. They refused to drink water from the same drum or eat food which was cooked and served in the same vessels that were used for the lower castes. But their protests came to no avail. On the ship, everyone was just a coolie, and all of them had to live in and share the same cramped space on the lower deck. Thousands of years of social structures and customs crumbled at the indenture altar. On the ship, they all blended into one shade: poor and desperate for a better life. They became jehaji bhai, ship brothers.

As with all sea journeys, some of the coolies fell sick for one reason or the other. Seasickness, food poisioning, and infections were common. On days when the ocean waves were choppy, the coolies had a tough time, especially the older coolies. When stormy waves rocked the ship, the coolies feared for their lives and kicked up a commotion. Some held onto the poles and would not let go even after the storm subsided. When it rained, everyone had to scramble to collect the water, empty it out, and clean up the deck. For those who fell ill along the way, the journey was miserable to say the least. Medicine was in short supply for it had to be saved lest the upper cabin passengers needed it.

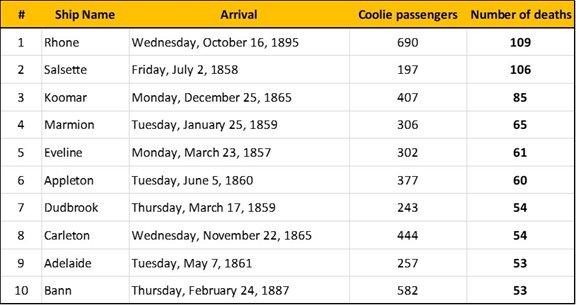

A number of coolies dies of illness on these journeys. It is heartbreaking to note that in some years, it was almost 20% of the passengers! Below is a list of the top 10 coolie fatalities during the journey to the carribean.

Pregnancies were not uncommon. If it was a still born baby or a coolie who died of illness, the sad ritual was to dispose of the bodies in the middle of the night by throwing them overboard.

Indenture officially ended in 1917. Towards the end of indenture, steam ships significantly reduced the time of travel and number of deaths and disease, but alas, the evolution of shipping technology came a little too late in the Indenture saga.